- Transhumaniste

-

Transhumanisme

Le transhumanisme est un mouvement culturel et intellectuel prônant l'usage des sciences et des technologies afin de développer les capacités physiques et mentales des êtres humains. Le transhumanisme considère certains aspects de la condition humaine tels que le handicap, la souffrance, la maladie, le vieillissement ou la mort subie comme inutiles et indésirables. Dans cette optique, les penseurs transhumanistes comptent sur les biotechnologies et sur d'autres technologies émergentes. Les dangers comme les avantages que présentent de telles évolutions préoccupent aussi le mouvement transhumaniste[1].

Le terme « transhumanisme » est symbolisé par « H+ » ou « h+ » et est souvent employé comme synonyme d'« amélioration humaine ». Bien que le premier usage connu du mot « transhumanisme » remonte à 1957, son sens actuel trouve son origine dans les années 1980, lorsque certains prospectivistes américains ont commencé à structurer ce qui est devenu le mouvement transhumaniste. Les penseurs transhumanistes prédisent que les être humains pourraient être capables de se transformer en êtres dotés de capacités telles qu'ils mériteraient l'étiquette de « posthumains »[1]. Ainsi, le transhumanisme est parfois considéré comme un posthumanisme ou encore comme une forme d'activisme caractérisé par une grande volonté de changement et influencé par les idéaux posthumanistes[2]

Les visions transhumanistes d'une humanité transformée ont suscité de nombreuses réactions tant positives que négatives émanant d'horizons de pensée très divers. Francis Fukuyama a ainsi déclaré, à propos du transhumanisme, qu'il s'agit de l'idée la plus dangereuse du monde[3], ce à quoi un de ses promoteurs, Ronald Bailey, répond que c'est, au contraire, le « mouvement qui incarne les aspirations les plus audacieuses, courageuses, imaginatives et idéalistes de l'humanité »[4].

Histoire

Selon les philosophes ayant étudié l'histoire du transhumanisme[1], celui-ci s'inscrit dans un courant de pensée remontant à l'Antiquité : la quête d'immortalité de l'Épopée de Gilgamesh ou les quêtes de la fontaine de Jouvence et de l'élixir de longue vie, au même titre que tous les efforts ayant visé à empêcher le vieillissement et la mort, en sont l'expression. La philosophie transhumaniste trouve cependant ses racines dans l'humanisme de la Renaissance et dans la philosophie des Lumières. Pic de la Mirandole appelle ainsi l'homme à « sculpter sa propre statue »[5]. Plus tard, Condorcet spécule quant à l'application possible des sciences médicales à l'extension infinie de la durée de vie humaine. Des réflexions du même ordre se retrouvent chez Benjamin Franklin, qui rêve de suspended animation ⇔ vie suspendue. Enfin, Charles Darwin écrit qu'il est très probable que l'humanité telle que nous la connaissons n'en soit pas au stade final de son évolution mais plutôt à une phase proche de son commencement[1]. Il faut en revanche mettre à part la pensée de Nietzsche, qui, s'il forge la notion de « surhomme », n'envisage absolument pas la possibilité d'une transformation technologique de l'Homme mais plutôt celle d'un épanouissement personnel[1].

Nikolai Fyodorov, un philosophe russe du XIXe siècle, soutenait l'idée d'un usage de la science à des fins d'extension radicale de la durée de vie, d'immortalité ou de résurrection des morts[6]. Au XXe siècle, le généticien J.B.S. Haldane, auteur de l'essai intitulé Daedalus: Science and the Future paru en 1923, est un pionnier influent de la pensée transhumaniste. En ligne directe avec le transhumanisme moderne, il annonce les considérables apports de la génétique et d'autres avancées de la science aux progrès de la biologie humaine et prévoit que ces avancées seront accueillies comme autant de blasphèmes et de perversions « indécentes et contre-nature ». J. D. Bernal spécule quant à la colonisation de l'espace, aux implants bioniques et aux améliorations cognitives qui sont des thèmes transhumanistes classiques depuis lors[1]. Le biologiste Julian Huxley, frère d'Aldous Huxley (un ami d'enfance de Haldane), semble être le premier à avoir utilisé le mot « transhumanisme ». En 1957, il définit le transhumain comme un « homme qui reste un homme, mais se transcende lui même en déployant de nouveaux possibles de et pour sa nature humaine »[7]. Cette définition diffère quelque peu de celle généralement acceptée depuis les années 1980.

Au début des années 1960, la question des relations entre les intelligences humaines et artificielles, qui est une des thématiques centrales du transhumanisme, est abordée par l'informaticien Marvin Minsky[8]. Dans les décennies qui suivent, ce domaine de recherches continue de voir apparaître d'influents penseurs, comme Hans Moravec ou Raymond Kurzweil, tantôt officiant dans des travaux d'ordre technique, tantôt spéculant sur l'avenir technologique, à la manière du transhumanisme[9][10] L'émergence d'un mouvement transhumaniste clairement identifiable commence dans les dernières décennies du XXe siècle. En 1966, FM-2030 (anciennement F.M. Esfandiary), un futurologue qui enseigne les « nouveaux concepts de l'Homme »[11] à la New School de New York, commence à identifier les personnes qui adoptent des technologies, des styles de vie et des conceptions du monde signalant une transition vers la posthumanité à des transhumains (mot-valise formé à partir de « humain transitoire »)[12] En 1972, Robert Ettinger contribue à la conceptualisation du transhumanisme dans son livre Man into Superman[13]. En 1973, FM-2030 publie le Upwingers Manifesto pour stimuler l'activisme transhumaniste[14]

Les premiers transhumanistes se reconnaissant comme tels se rencontrent au début des années 1980 à l'université de Californie à Los Angeles, qui devient le centre principal de la pensée transhumaniste. À cette occasion, FM-2030 tient une conférence sur son idéologie futuriste de la « Troisième Voie » (Third Way). Dans les locaux de EZTV, alors couramment fréquentés par les transhumanistes et futurologues, Natasha Vita-More présente un film expérimental, intitulé Breaking Away, développant le thème d'humains rompant avec leurs limites biologiques et avec la gravité terrestre en allant dans l'espace[15],[16]. FM-2030 et Vita-More commencent rapidement à organiser d'autres réunions transhumanistes à Los Angeles, rassemblant notamment les étudiants de FM-2030 d'une part et le public attiré par les productions artistiques de Vita-More d'autre part. En 1982, Vita-More rédige le Transhumanist Arts Statement[17] (Traité d'Arts Transhumanistes), et, six ans après, produit une émission de télévision sur la transhumanité, TransCentury Update, qui est suivie par plus de 100 000 téléspectateurs.

En 1986, Eric Drexler publie Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology, [18], qui analyse les perspectives liées aux nanotechnologies et aux assembleurs moléculaires, et fonde l'Institut Foresight. Les bureaux de Californie du sud de l'Alcor Life Extension Foundation, la première organisation à but non lucratif effectuant des recherches sur la cryonie et œuvrant pour sa promotion et sa mise en œuvre, devinrent également un lieu de regroupement privilégié des futuristes. En 1988, le premier numéro d'Extropy Magazine fut publié par Max More et Tom Morrow. En 1990, More créa sa propre doctrine transhumaniste qu'il exprima sous la forme des Principles of Extropy (« Principes de l'Extropie »)[19], et jeta les bases du transhumanisme moderne en lui donnant une nouvelle définition[20] :

« Le transhumanisme est une classe de philosophies ayant pour but de nous guider vers une condition posthumaine. Le transhumanisme partage de nombreuses valeurs de l'humanisme parmi lesquelles un respect de la raison et de la science, un attachement au progrès et une grande considération pour l'existence humaine (ou transhumaine) dans cette vie. […] Le transhumanisme diffère de l'humanisme en ce qu'il reconnaît et anticipe les changements radicaux de la nature et des possibilités de la vie de l'homme provoqués par diverses sciences et technologies […]. »En 1992, More et Morrow fondent l'Extropy Institute qui a pour but de densifier le réseau social futuriste et de promouvoir une réflexion collective sur les new memeplexes ⇔ idéologies à venir en organisant une série de conférences et, surtout, en rédigeant un carnet d'adresses : en conséquence, la pensée transhumaniste se voit diffusée pour la première fois, pendant la période d'essor de la cyberculture et de la contreculture cyberdélique. En 1998, les philosophes Nick Bostrom et David Pearce fondent la World Transhumanist Association (WTA), une organisation non-gouvernementale d'échelle internationale œuvrant afin que le transhumanisme soit reconnu comme digne d'intérêt par le milieu scientifique comme par les pouvoirs publics[21]. En 1999, la WTA rédige et adopte la Déclaration Transhumaniste (The Transhumanist Declaration).[22]. La FAQ Transhumaniste, conçue par la WTA, donne deux définitions formelles du transhumanisme[23] :

«- Le mouvement culturel et intellectuel qui affirme la possibilité et la désirabilité d'une amélioration fondamentale de la condition humaine par l'usage de la raison, en particulier en développant et diffusant largement les technologies visant à éliminer le vieillissement et à améliorer de manière significative les capacités intellectuelles, physiques et psychologies de l'être humain.

- L'étude des répercussions, des promesses et des dangers potentiels de technologies qui nous permettront de surpasser des contraintes inhérentes à la nature humaine ainsi que l'étude des problèmes éthiques que soulèvent l'élaboration et l'usage de telles technologies. »

Anders Sandberg, un universitaire et éminent transhumaniste, a recueilli un certain nombre de définitions similaires[24].

Les représentants de la WTA considéraient que les forces sociales constituaient un frein potentiel à leurs projets futuristes et qu'il fallait, par conséquent, statuer sur la position à adopter face à elles, mais toutes les organisations transhumanistes ne pensaient pas nécessairement ainsi[25]. En particulier, un problème posé était celui de l'accès équitable des individus de classes sociales et de nationalités différentes à la technologie d'amélioration humaine[26]. En 2006, après une lutte politique dans les rangs du mouvement transhumaniste entre la droite libertarienne et la gauche libérale, la WTA, sous l'égide de son ancien directeur James Hughes, a adopté une posture plus proche du centre-gauche[27],[26]. Toujours en 2006, le conseil d'administration de l'Extropy Institute mit un terme à ses activités, déclarant que sa mission était "essentiellement remplie"[28]. La WTA a donc pris la place de principale organisation transhumaniste mondiale. En 2008, afin de changer son image, la WTA adopta le nom de « Humanity Plus » afin de donner une image de plus grandes valeurs humaine[29]. Humanity Plus publie H+ Magazine, un périodique publié par R. U. Sirius et qui présente des actualités et des idées du transhumanisme[30],[31].

Théorie

Article détaillé : Liste des thèmes transhumanistes.La question de la vision du transhumanisme comme une branche du posthumanisme et celle de la conceptualisation du posthumanisme relativement au transhumanisme font débat. Les critiques du transhumanisme, conservateurs[3], chrétiens[32] ou progressistes[33],[34], le perçoivent souvent comme une variante ou une forme plus activiste du posthumanisme, mais des érudits pro-transhumanisme le qualifient aussi de branche de la « philosophie posthumaniste », par exemple[2]. Une propriété commune au transhumanisme et au posthumanisme philosophique est la vision future de nouvelles espèces intelligentes, évolutions de l'humanité, qui la complèteront ou la supplanteront. Le transhumanisme met l'accent sur l'aspect évolutionniste du phénomène, envisageant la création d'un animal doté d'une très grande intelligence grâce à l'amélioration cognitive (c'est-à-dire grâce à la provolution)[25], mais se raccroche à un « futur posthumain », finalité d'une évolution artificiellement perpétrée[35].

Cependant, l'idée de créer des êtres intelligents artificiels proposée, par exemple, par le roboticien Hans Moravec, a influencé le transhumanisme[9]. Mais les idées de Moravec et le transhumanisme se sont aussi vus dépeints comme une variante « complaisante » ou « apocalyptique » du posthumanisme et ainsi distingués du « posthumanisme culturel » dans les lettres et les arts[36]. Un tel « posthumanisme critique » fournirait matière à repenser les relations entre humains et machines de plus en plus sophistiquées alors que, dans cette perspective, le transhumanisme et les posthumanismes similaires n'abandonnent pas les concepts désuets de l'« individu libre et autonome » mais étendent ses prérogatives au domaine du posthumain[37]. C'est dans ce cadre de pensée que le transhumanisme se décrit parfois lui-même comme une continuation de l'humanisme et de l'esprit des Lumières. self-characterisations ⇔ merci d'apporter votre expertise, et de préciser

Certains humanistes laïques voient dans le transhumanisme la progéniture du mouvement de libre-pensée. Ils soutiennent que les transhumanistes se distinguent des humanistes traditionnels en ce qu'ils se concentrent tout particulièrement sur les apports de la technologie aux problèmes humains et au problème de la mort[38]. Cependant, d'autres progressistes affirment que le posthumanisme, philosophique comme activiste, se détourne des préoccupations de justice sociale, de réforme des institutions humaines et d'autres centres d'intérêt des Lumières et incarne en fait un désir narcissique de transcendance du corps humain, en quête d'une manière d'être plus intense, plus vive, plus exquise[39]. De ce point de vue, le transhumanisme abandonne les visées de l'humanisme, de la philosophie des Lumières et des politiques progressistes.

Buts

Bien que de nombreux théoriciens et partisans du transhumanisme cherchent à exploiter la raison, la science et la technologie afin de contrer la pauvreté, la maladie, le handicap et l'insuffisance alimentaire dans le monde, le transhumanisme, lui, se distingue par l'intérêt particulier qu'il porte à l'application des technologies à l'amélioration du corps humain à l'échelle individuelle. Beaucoup de transhumanistes contribuent activement à l'estimation des apports possibles des technologies futures et des systèmes sociaux innovants à la qualité du vivant en général, tout en recherchant la réalisation pratique, par l'élimination des barrières congénitales du physique et du mental, de l'idéal d'égalité aux sens légal et politique.

Les philosophes transhumanistes soutiennent qu'il n'existe pas seulement un impératif éthique du perfectionnisme, dont les humains s'efforce au progrès et l'amélioration de la condition humaine, mais aussi qu'il soit possible et souhaitable que l'humanité commence à une ère transhumain, dont les humains ont contrôle de son évolution. Dans une telle ère, l'évolution naturel serait remplacée avec le changement délibéré.

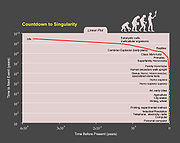

Certains théoriciens, comme Raymond Kurzweil, considèrent que le rythme du changement technologique est en train de s'accélerer et que les cinquante prochaines années verront apparaitre non seulement des avancées technologiques radicales mais aussi une singularité technologique, un point d'inflexion qui changera la nature même de l'homme.[40] . La plupart des transhumanistes considèrent cette rupture comme désirable mais mettent en garde contre les dangers inhérents à une accéleration brutale du progrès technologique. Ainsi, ils jugent la responsalité de tous les acteurs de ce progrès comme nécessaire pour éviter toute dérive grave. Par exemple, Bostrom a abondemment écrit sur le [existential risk] portant sur la santé future de l'humanité, y compris les risques qui pourraient découler de l'émergence des nouvelles technologies. [41]

Ethique

Les transhumanistes s'engagent dans des approches interdisciplinaires pour comprendre et évaluer les possibilités de dépasser les limitations biologiques. Ils s'appuient sur la futurologie dont les divers domaines de l'éthique tels que la bioéthique, l'infoéthique, la nanoéthique, la neuroéthique, la roboéthique, et la technoéthique proviennent principalement mais pas exclusivement d'une philosophie utilitaire, et d'une perspective libérale du progrès social, politique et économique. Contrairement à beaucoup de philosophes, critiques sociaux, et activistes qui placent une valeur morale sur la préservation des systèmes naturels, les transhumanistes voient au mieux le concept spécifique de ce qui est "naturel" comme problématiquement nébuleux, et au pire comme un obstacle au progrès.[42] En relation avec cela, beaucoup des principaux défenseurs du transhumanisme jugent les critiques de ce dernier provenants de la droite et de la gauche politique, comme "bioconservateurs", ou "néo-luddistes", ce dernier terme faisant allusion au mouvement social du 19e siècle de l'anti-industrialisation, opposé au remplacement des travailleurs humains par des machines.[43]

Courants de pensées

Il y a une variété d'opinions au sein de la pensée transhumaniste. Beaucoup des principaux penseurs transhumanistes ont des vues qui sont constamment révisées et en développement.[44] Quelques courants distinctifs du transhumanisme sont identifiés et listés ici dans l'ordre alphabétique :

- L'abolitionisme (impératif hédoniste)[45]

- Le transhumanisme démocratique, synthèse de la démocratie libérale, de la social-démocratie et du transhumanisme.[46]

- L'extropianisme

- L'immortalisme basé sur l'idée que l'immortalité est technologiquement possible et désirable.[47]

- Le postsexualisme

- Le singularitarianisme basé sur l'idée qu'une singularité technologique est possible et souhaitable.[40]

- Le technogaïanisme, une démarche écologique basé sur l'idée que le progrès technologique peut permettre de restaurer l'écosystème notamment par le biais des technologies alternatives.[46]

- Le transhumanisme anarchiste

- Le transhumanisme libertarien

Spiritualité

Bien que quelques transhumanistes disent secular spirituality ⇔ adhérer à une idéologie spirituelle sans appartenir à une structure religieuse, ils sont pour la plupart athées.[21] Une minorité de transhumanistes, cependant, suivent des formes libérales de traditions de la philosophie orientale comme le bouddhisme et le yoga[48] ou ont fait merger leurs idées transhumanistes avec des religions occidentales établies telles que le christiannisme libéral[49] ou le mormonisme[50]. En dépit de l'attitude séculaire qui est prévalente, quelques transhumanistes entretiennent des espoirs traditionnellement épousés par les religions, comme l'immortalité,[47] pendant que de nouveaux mouvements religieux controversés, nés vers la fin du 20e siècle, ont explicitement embrassés les buts transhumanistes de transformation de la condition humaine, en applicant la technologie d'altération du corps et de l'esprit, tel que le mouvement raëlien.[51] Cependant, la plupart des penseurs associés avec le mouvement transhumaniste se focalisent sur les buts pratiques de l'utilisation de la technologie pour aider à avoir des vies plus longues et en meilleure santé ; tout en spéculant sur le fait que la compréhension future de la neurothéologie et de l'application de la neurotechnologie permettraient aux humains de gagner un plus grand contrôle sur les états modifiés de conscience, qui sont communément interprétés comme des "expériences spirituelles", et permettraient ainsi d'accéder à une connaissance de soi plus profonde.[48]

La majorité des transhumanistes sont des matérialistes qui ne croient pas en une âme humaine transcendante. La théorie de la personnalité transhumaniste est également contre l'identification unique des acteurs moraux et des sujets avec les humains biologiques, jugeant comme antispéciste l'exclusion des non-humains, des para-humains et des machines sophistiquées, d'un point de vue éthique.[52] Beaucoup croient en la compatibilité entre les esprits humains et le matériel informatique, avec l'implication théorique que la conscience humaine serait un jour transférée dans des médias alternatifs, une technique spéculative communément connue comme "téléchargement de l'esprit".[53] Une formulation extrême de cette idée peut-être trouvée dans la proposition de Frank Tipler du point Omega. En s'inspirant d'idées du digitalisme, Tipler a avancé l'idée que l'effrondement de l'Univers dans des milliards d'années pourrait créer les conditions pour la perpétuation de l'humanité dans une réalité simulée à l'intérieur d'un mégaordinateur, et achèverait ainsi la forme du "Dieu post-humain". Bien que n'étant pas un transhumaniste, la pensée de Tipler a été inspirée par les écrits de Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, un paléontologue et théologien jésuite qui a vu une cause finale évoluante dans le développement d'une noosphère, une conscience globale.[54]

L'idée de télécharger une personnalité dans un substrat non-biologique et ses hypothèses sous-jacentes sont critiquées par un large panel d'universitaires, scientifiques et activistes, quelques fois à l'égard du transhumanisme lui-même, quelques fois à l'égard de penseurs tels que Marvin Minsky ou Hans Moravec qui sont souvent vus comme ses initiateurs. Relativement aux hypothèses sous-jacentes, comme par exemple l'héritage de la cybernétique, certains ont fait valoir que cet espoir matérialiste engendre un monisme spirituel, une variante de l'idéalisme philosophique.[55] Vu d'une perspective conservatrice chrétienne, l'idée de télécharger l'esprit est affirmée comme représentant une dénigration du corps humain caractéristique de la croyance gnostique.[56] Le transhumanisme et ses progéniteurs intellectuels présumés ont aussi été décrits comme "néo-gnostiques" par les commentateurs non-chrétiens et séculaires.[57][58]

Le premier dialogue entre le transhumanisme et la foi était l'objectif d'un séminaire académique ayant eu lieu à l'Université de Toronto en 2004.[59] Parce que cela pourrait servir quelques-unes des mêmes fonctions que les gens ont traditionnellement vu dans la religion, les religieux et critiques séculaires ont maintenu que le transhumanisme était lui-même une religion ou, au minimum, une pseudoreligion. Les critiques religieuses à elles-seules ont mis en faute la philosophie du transhumanisme comme n'offrant aucune vérité éternelle ni une relation avec le divin. Elles ont commenté qu'une philosophie dépossédée de ces croyances laisse l'humanité à la dérive dans une mer brumeuse du cynisme postmoderne et de l'anomie. Les transhumanistes ont répondu que de telles critiques reflètent un échec du regard sur le contenu actuel de la philosophie transhumaniste, qui loin d'être cynique, est enraciné dans des attitudes optimistes, idéalistes, qui nous ramènent aux Lumières.[60] Suivant ce dialogue, William Sims Bainbridge a conduit une étude pilote, publiée dans le journal de l'évolution et de la technologie, suggérant que les attitudes religieuses sont négativement corrélées avec l'acceptation des idées transhumanistes, et indiquant que les individus avec des visions du monde très religieuses tendent à percevoir le transhumanisme comme étant un affront direct, compétitif (bien que ultimement futile), de leurs croyances spirituelles.[61]

Pratique

Pendant que quelques transhumanistes prennent une approche abstraite et théorique pour les bénéfices perçus des technologies émergentes, d'autres ont donné des propositions précises pour des modifications du corps humain, incluant celles qui sont héréditaires. Les transhumanistes sont souvent concernés avec les méthodes d'amélioration du système nerveux humain. Bien que certains proposent la modification du système nerveux périphérique, le cerveau est considéré comme le dénominateur commun de la personnalité et est donc l'objectif principal des ambitions transhumanistes.[62]

En tant que partisans du développement personnel et des modifications corporelles, les transhumanistes tendent à utiliser les technologies et techniques existantes qui sont supposées améliorer les performances cognitives et physiques, pendant qu'ils s'engagent dans des routines et styles de vie faits pour améliorer la santé et la longévité.[63] Selon leur âge, quelques transhumanistes expriment leur préoccupation sur le fait qu'ils ne vivront pas pour récolter les bénéfices des futures technologies. Cependant, beaucoup ont un grand intérêt dans les stratégies d'extension de la vie, et dans le financement de recherches dans la cryonie, de sorte à faire de ce dernier une option viable de dernier recours plutôt que de la laisser comme méthode non éprouvée.[64] Les réseaux et communautés transhumanistes régionaux et globaux avec une gamme d'objectifs existent pour fournir de l'aide, des forums pour discuter et des projets collaboratifs.

Technologies of interest

Article principal : Human enhancement technologies. Converging Technologies, a 2002 report exploring the potential for synergy among nano-, bio-, info- and cogno-technologies, has become a landmark in near-future technological speculation.

Converging Technologies, a 2002 report exploring the potential for synergy among nano-, bio-, info- and cogno-technologies, has become a landmark in near-future technological speculation.

Transhumanists support the emergence and convergence of technologies such as nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technology and cognitive science (NBIC), and hypothetical future technologies such as simulated reality, artificial intelligence, superintelligence, mind uploading, and cryonics. They believe that humans can and should use these technologies to become more than human.[65] They therefore support the recognition and/or protection of cognitive liberty, morphological freedom, and procreative liberty as civil liberties, so as to guarantee individuals the choice of using human enhancement technologies on themselves and their children.[66] Some speculate that human enhancement techniques and other emerging technologies may facilitate more radical human enhancement by the midpoint of the 21st century.[40]

A 2002 report, Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance, commissioned by the National Science Foundation and US Department of Commerce, contains descriptions and commentaries on the state of NBIC science and technology by major contributors to these fields. The report discusses potential uses of these technologies in implementing transhumanist goals of enhanced performance and health, and ongoing work on planned applications of human enhancement technologies in the military and in the rationalization of the human-machine interface in industry.[67]

While international discussion of the converging technologies and NBIC concepts includes strong criticism of their transhumanist orientation and alleged science fictional character,[68][69][70] research on brain and body alteration technologies has accelerated under the sponsorship of the US Department of Defense, which is interested in the battlefield advantages they would provide to the "supersoldiers" of the United States and its allies.[71]

Arts and culture

Articles principaux : Transhumanism in fiction et Transhumanist art.Transhumanist themes have become increasingly prominent in various literary forms during the period in which the movement itself has emerged. Contemporary science fiction often contains positive renditions of technologically enhanced human life, set in utopian (especially techno-utopian) societies. However, science fiction's depictions of enhanced humans or other posthuman beings frequently come with a cautionary twist. The more pessimistic scenarios include many horrific or dystopian tales of human bioengineering gone wrong. In the decades immediately before transhumanism emerged as an explicit movement, many transhumanist concepts and themes began appearing in the speculative fiction of authors such as Robert A. Heinlein (Lazarus Long series, 1941–87), A. E. van Vogt (Slan, 1946), Isaac Asimov (I, Robot, 1950), Arthur C. Clarke (Childhood's End, 1953) and Stanislaw Lem (Cyberiad, 1967).[25]

The cyberpunk genre, exemplified by William Gibson's Neuromancer (1984) and Bruce Sterling's Schismatrix (1985), has particularly been concerned with the modification of human bodies. Other novels dealing with transhumanist themes that have stimulated broad discussion of these issues include Blood Music (1985) by Greg Bear, The Xenogenesis Trilogy (1987–1989) by Octavia Butler; The Beggar's Trilogy (1990–94) by Nancy Kress; much of Greg Egan's work since the early 1990s, such as Permutation City (1994) and Diaspora (1997); The Bohr Maker (1995) by Linda Nagata; Oryx and Crake (2003) by Margaret Atwood; The Elementary Particles (Eng. trans. 2001) and The Possibility of an Island (Eng. trans. 2006) by Michel Houellebecq; and Glasshouse (2005) by Charles Stross. Many of these works are considered part of the cyberpunk genre or its postcyberpunk offshoot.

Fictional transhumanist scenarios have also become popular in other media during the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries. Such treatments are found in comic books (Captain America, 1941; Him, 1967; Transmetropolitan, 1997), films (2001 : L'Odyssée de l'espace, 1968; Blade Runner, 1982; Gattaca, 1997; REPO! the Genetic Opera, 2008), television series (the Cybermen of Doctor Who, 1966; The Six Million Dollar Man, 1973; the Borg of Star Trek: The Next Generation, 1989; manga and anime (Galaxy Express 999, 1978; Appleseed, 1985; Ghost in the Shell, 1989 and Gundam Seed, 2002), computer games (Metal Gear Solid, 1998; Deus Ex, 2000; Half-Life 2, 2004; and BioShock, 2007), et jeux de rôles (Shadowrun, 1989), Transhuman Space, 2002)

In addition to the work of Natasha Vita-More, curator of the Transhumanist Arts & Culture center, transhumanist themes appear in the visual and performing arts.[72] Carnal Art, a form of sculpture originated by the French artist Orlan, uses the body as its medium and plastic surgery as its method.[73] Commentators have pointed to American performer Michael Jackson as having used technologies such as plastic surgery, skin-lightening drugs and hyperbaric oxygen therapy over the course of his career, with the effect of transforming his artistic persona so as to blur identifiers of gender, race and age.[74] The work of the Australian artist Stelarc centers on the alteration of his body by robotic prostheses and tissue engineering.[75] Other artists whose work coincided with the emergence and flourishing of transhumanism and who explored themes related to the transformation of the body are the Yugoslavian performance artist Marina Abramovic and the American media artist Matthew Barney. A 2005 show, Becoming Animal, at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, presented exhibits by twelve artists whose work concerns the effects of technology in erasing boundaries between the human and non-human.

Controversy

Transhumanist thought and research depart significantly from the mainstream and often directly challenges orthodox theories. The very notion and prospect of human enhancement and related issues also arouse public controversy.[76] Criticisms of transhumanism and its proposals take two main forms: those objecting to the likelihood of transhumanist goals being achieved (practical criticisms); and those objecting to the moral principles or world view sustaining transhumanist proposals or underlying transhumanism itself (ethical criticisms). However, these two strains sometimes converge and overlap, particularly when considering the ethics of changing human biology in the face of incomplete knowledge.

Critics or opponents often see transhumanists' goals as posing threats to human values. Some also argue that strong advocacy of a transhumanist approach to improving the human condition might divert attention and resources from social solutions. As most transhumanists support non-technological changes to society, such as the spread of civil rights and civil liberties, and most critics of transhumanism support technological advances in areas such as communications and health care, the difference is often a matter of emphasis. Sometimes, however, there are strong disagreements about the very principles involved, with divergent views on humanity, human nature, and the morality of transhumanist aspirations. At least one public interest organization, the U.S.-based Center for Genetics and Society, was formed, in 2001, with the specific goal of opposing transhumanist agendas that involve transgenerational modification of human biology, such as full-term human cloning and germinal choice technology. The Institute on Biotechnology and the Human Future of the Chicago-Kent College of Law critically scrutinizes proposed applications of genetic and nanotechnologies to human biology in an academic setting.

Some of the most widely known critiques of the transhumanist program refer to novels and fictional films. These works of art, despite presenting imagined worlds rather than philosophical analyses, are used as touchstones for some of the more formal arguments.

Infeasibility (Futurehype argument)

In his 1992 book Futurehype: The Tyranny of Prophecy, sociologist Max Dublin points out many past failed predictions of technological progress and argues that modern futurist predictions will prove similarly inaccurate. He also objects to what he sees as scientism, fanaticism, and nihilism by a few in advancing transhumanist causes, and writes that historical parallels exist to millenarian religions and Communist doctrines.[77] Several notable transhumanists have predicted that death-defeating technologies will arrive (usually late) within their own conventionally-expected lifetimes. Wired magazine founding executive editor Kevin Kelly has argued these transhumanists have overly optimistic expectations of when dramatic technological breakthroughs will occur because they hope to be saved from their own deaths by those developments.[78]

Some transhumanist thinkers assert the pace of technological innovation is accelerating and that the next 50 years may yield not only radical technological advances but possibly a technological singularity

Some transhumanist thinkers assert the pace of technological innovation is accelerating and that the next 50 years may yield not only radical technological advances but possibly a technological singularity

Despite his sympathies for transhumanism, in his 2002 book Redesigning Humans: Our Inevitable Genetic Future, public health professor Gregory Stock is skeptical of the technical feasibility and mass appeal of the cyborgization of humanity predicted by Raymond Kurzweil, Hans Moravec and Kevin Warwick. He believes that throughout the 21st century, many humans will find themselves deeply integrated into systems of machines, but will remain biological. Primary changes to their own form and character will arise not from cyberware but from the direct manipulation of their genetics, metabolism, and biochemistry.[79]

In his 2006 book Future Hype: The Myths of Technology Change, computer scientist and engineer Bob Seidensticker argues that today's technological achievements are not unprecedented. Exposing major myths of technology and examining the history of high tech hype, he aims to uncover inaccuracies and misunderstandings that may characterise the popular and transhumanist views of technology, to explain how and why these views have been created, and to illustrate how technological change in fact proceeds.[80]

Those thinkers who defend the likelihood of massive technological change within a relatively short timeframe emphasize what they describe as a past pattern of exponential increases in humanity's technological capacities. This emphasis appears in the work of popular science writer Damien Broderick, notably his 1997 book, The Spike, which contains his speculations about a radically changed future. Kurzweil develops this position in much detail in his 2005 book, The Singularity Is Near. Broderick points out that many of the seemingly implausible predictions of early science fiction writers have, indeed, come to pass, among them nuclear power and space travel to the moon. He also claims that there is a core rationalisme to current predictions of very rapid change, asserting that such observers as Kurzweil have a good track record in predicting the pace of innovation.[81]

Hubris (Playing God argument)

There are two distinct categories of criticism, theological and secular, that have been referred to as "playing god" arguments:

The first category is based on the alleged inappropriateness of humans substituting themselves for an actual god. This approach is exemplified by the 2002 Vatican statement Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God, [82] in which it is stated that, "Changing the genetic identity of man as a human person through the production of an infrahuman being is radically immoral", implying, as it would, that "man has full right of disposal over his own biological nature". At the same time, this statement argues that creation of a superhuman or spiritually superior being is "unthinkable", since true improvement can come only through religious experience and "realizing more fully the image of God". Christian theologians and lay activists of several churches and denominations have expressed similar objections to transhumanism and claimed that Christians already enjoy, however post mortem, what radical transhumanism promises such as indefinite life extension or the abolition of suffering. In this view, transhumanism is just another representative of the long line of utopian movements which seek to immanentize the eschaton i.e. try to create "heaven on earth".[83][84]

The second category is aimed mainly at "algeny", which Jeremy Rifkin defined as "the upgrading of existing organisms and the design of wholly new ones with the intent of 'perfecting' their performance",[85] and, more specifically, attempts to pursue transhumanist goals by way of genetically modifying human embryos in order to create "designer babies". It emphasizes the issue of biocomplexity and the unpredictability of attempts to guide the development of products of biological evolution. This argument, elaborated in particular by the biologist Stuart Newman, is based on the recognition that the cloning and germline genetic engineering of animals are error-prone and inherently disruptive of embryonic development. Accordingly, so it is argued, it would create unacceptable risks to use such methods on human embryos. Performing experiments, particularly ones with permanent biological consequences, on developing humans, would thus be in violation of accepted principles governing research on human subjects (see the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki). Moreover, because improvements in experimental outcomes in one species are not automatically transferable to a new species without further experimentation, there is claimed to be no ethical route to genetic manipulation of humans at early developmental stages.[86]

As a practical matter, however, international protocols on human subject research may not present a legal obstacle to attempts by transhumanists and others to improve their offspring by germinal choice technology. According to legal scholar Kirsten Rabe Smolensky, existing laws would protect parents who choose to enhance their child's genome from future liability arising from adverse outcomes of the procedure.[87]

Religious thinkers allied with transhumanist goals, such as the theologians Ronald Cole-Turner and Ted Peters, reject the first argument, holding that the doctrine of "co-creation" provides an obligation to use genetic engineering to improve human biology.[88][89]

Transhumanists and other supporters of human genetic engineering do not dismiss the second argument out of hand, insofar as there is a high degree of uncertainty about the likely outcomes of genetic modification experiments in humans. However, bioethicist James Hughes suggests that one possible ethical route to the genetic manipulation of humans at early developmental stages is the building of computer models of the human genome, the proteins it specifies, and the tissue engineering he argues that it also codes for. With the exponential progress in bioinformatics, Hughes believes that a virtual model of genetic expression in the human body will not be far behind and that it will soon be possible to accelerate approval of genetic modifications by simulating their effects on virtual humans.[25] Public health professor Gregory Stock points to artificial chromosomes as an alleged safer alternative to existing genetic engineering techniques.[79] Transhumanists therefore argue that parents have a moral responsibility called procreative beneficence to make use of these methods, if and when they are shown to be reasonably safe and effective, to have the healthiest children possible. They add that this responsibility is a moral judgment best left to individual conscience rather than imposed by law, in all but extreme cases. In this context, the emphasis on freedom of choice is called procreative liberty.[25]

Contempt for the flesh (Fountain of Youth argument)

Philosopher Mary Midgley, in her 1992 book Science as Salvation, traces the notion of achieving immortality by transcendence of the material human body (echoed in the transhumanist tenet of mind uploading) to a group of male scientific thinkers of the early 20th century, including J.B.S. Haldane and members of his circle. She characterizes these ideas as "quasi-scientific dreams and prophesies" involving visions of escape from the body coupled with "self-indulgent, uncontrolled power-fantasies". Her argument focuses on what she perceives as the pseudoscientific speculations and irrational, fear-of-death-driven fantasies of these thinkers, their disregard for laymen, and the remoteness of their eschatological visions.[90] Many transhumanists see the 2006 film The Fountain's theme of nécrophobie and critique of the quixotic quest for eternal youth as depicting some of these criticisms.[91]

What is perceived as contempt for the flesh in the writings of Marvin Minsky, Hans Moravec, and some transhumanists, has also been the target of other critics for what they claim to be an instrumental conception of the human body.[37] Reflecting a strain of feminist criticism of the transhumanist program, philosopher Susan Bordo points to "contemporary obsessions with slenderness, youth, and physical perfection", which she sees as affecting both men and women, but in distinct ways, as "the logical (if extreme) manifestations of anxieties and fantasies fostered by our culture.”[92] Some critics question other social implications of the movement's focus on body modification. Political scientist Klaus-Gerd Giesen, in particular, has asserted that transhumanism's concentration on altering the human body represents the logical yet tragic consequence of atomized individualism and body commodification within a consumer culture.[57]

Nick Bostrom asserts that the desire to regain youth, specifically, and transcend the natural limitations of the human body, in general, is pan-cultural and pan-historical, and is therefore not uniquely tied to the culture of the 20th century. He argues that the transhumanist program is an attempt to channel that desire into a scientific project on par with the Human Genome Project and achieve humanity's oldest hope, rather than a puerile fantasy or social trend.[1]

Trivialization of human identity (Enough argument)

In the US, the Amish are a religious group probably most known for their avoidance of certain modern technologies. Transhumanists draw a parallel by arguing that in the near-future there will probably be "Humanish", people who choose to "stay human" by not adopting human enhancement technologies, whose choice they believe must be respected and protected.[93]

In the US, the Amish are a religious group probably most known for their avoidance of certain modern technologies. Transhumanists draw a parallel by arguing that in the near-future there will probably be "Humanish", people who choose to "stay human" by not adopting human enhancement technologies, whose choice they believe must be respected and protected.[93]

In his 2003 book Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age, environmental ethicist Bill McKibben argued at length against many of the technologies that are postulated or supported by transhumanists, including germinal choice technology, nanomédecine and life extension strategies. He claims that it would be morally wrong for humans to tamper with fundamental aspects of themselves (or their children) in an attempt to overcome universal human limitations, such as vulnerability to aging, maximum life span, and biological constraints on physical and cognitive ability. Attempts to "improve" themselves through such manipulation would remove limitations that provide a necessary context for the experience of meaningful human choice. He claims that human lives would no longer seem meaningful in a world where such limitations could be overcome technologically. Even the goal of using germinal choice technology for clearly therapeutic purposes should be relinquished, since it would inevitably produce temptations to tamper with such things as cognitive capacities. He argues that it is possible for societies to benefit from renouncing particular technologies, using as examples Ming China, Tokugawa Japan and the contemporary Amish.[94]

Transhumanists and other supporters of technological alteration of human biology, such as science journalist Ronald Bailey, reject as extremely subjective the claim that life would be experienced as meaningless if some human limitations are overcome with enhancement technologies. They argue that these technologies will not remove the bulk of the individual and social challenges humanity faces. They suggest that a person with greater abilities would tackle more advanced and difficult projects and continue to find meaning in the struggle to achieve excellence. Bailey also claims that McKibben's historical examples are flawed, and support different conclusions when studied more closely.[95] For example, few groups are more cautious than the Amish about embracing new technologies, but though they shun television and use horses and buggies, some are welcoming the possibilities of gene therapy since inbreeding has afflicted them with a number of rare genetic diseases.[79]

Genetic divide (Gattaca argument)

Some critics of libertarian transhumanism have focused on its likely socioeconomic consequences in societies in which divisions between rich and poor are on the rise. Bill McKibben, for example, suggests that emerging human enhancement technologies would be disproportionately available to those with greater financial resources, thereby exacerbating the gap between rich and poor and creating a "genetic divide".[94] Lee M. Silver, a biologist and science writer who coined the term "reprogenetics" and supports its applications, has nonetheless expressed concern that these methods could create a two-tiered society of genetically-engineered "haves" and "have nots" if social democratic reforms lag behind implementation of enhancement technologies.[96] Critics who make these arguments do not thereby necessarily accept the transhumanist assumption that human enhancement is a positive value; in their view, it should be discouraged, or even banned, because it could confer additional power upon the already powerful. The 1997 film Gattaca's depiction of a dystopian society in which one's social class depends entirely on genetic modifications is often cited by critics in support of these views.[25]

These criticisms are also voiced by non-libertarian transhumanist advocates, especially self-described democratic transhumanists, who believe that the majority of current or future social and environmental issues (such as unemployment and resource depletion) need to be addressed by a combination of political and technological solutions (such as a guaranteed minimum income and alternative technology). Therefore, on the specific issue of an emerging genetic divide due to unequal access to human enhancement technologies, bioethicist James Hughes, in his 2004 book Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future, argues that progressives or, more precisely, techno-progressives must articulate and implement public policies (such as a universal health care voucher system that covers human enhancement technologies) in order to attenuate this problem as much as possible, rather than trying to ban human enhancement technologies. The latter, he argues, might actually worsen the problem by making these technologies unsafe or available only to the wealthy on the local black market or in countries where such a ban is not enforced.[25]

Threats to morality and democracy (Brave New World argument)

Various arguments have been made to the effect that a society that adopts human enhancement technologies may come to resemble the dystopia depicted in the 1932 novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. Sometimes, as in the writings of Leon Kass, the fear is that various institutions and practices judged as fundamental to civilized society would be damaged or destroyed.[97] In his 2002 book Our Posthuman Future and in a 2004 Foreign Policy magazine article, political economist and philosopher Francis Fukuyama designates transhumanism the world's most dangerous idea because he believes that it may undermine the egalitarian ideals of liberal democracy, through a fundamental alteration of "human nature".[3] Social philosopher Jürgen Habermas makes a similar argument in his 2003 book The Future of Human Nature, in which he asserts that moral autonomy depends on not being subject to another's unilaterally imposed specifications. Habermas thus suggests that the human "species ethic" would be undermined by embryo-stage genetic alteration.[98] Critics such as Kass, Fukuyama, and a variety of Christian authors hold that attempts to significantly alter human biology are not only inherently immoral but also threats to the social order. Alternatively, they argue that implementation of such technologies would likely lead to the "naturalizing" of social hierarchies or place new means of control in the hands of totalitarian regimes. The AI pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum criticizes what he sees as misanthropic tendencies in the language and ideas of some of his colleagues, in particular Marvin Minsky and Hans Moravec, which, by devaluing the human organism per se, promotes a discourse that enables divisive and undemocratic social policies.[99]

In a 2004 article in Reason, science journalist Ronald Bailey has contested the assertions of Fukuyama by arguing that political equality has never rested on the facts of human biology. He asserts that liberalism was founded not on the proposition of effective equality of human beings, or de facto equality, but on the assertion of an equality in political rights and before the law, or de jure equality. Bailey asserts that the products of genetic engineering may well ameliorate rather than exacerbate human inequality, giving to the many what were once the privileges of the few. Moreover, he argues, "the crowning achievement of the Enlightenment is the principle of tolerance". In fact, he argues, political liberalism is already the solution to the issue of human and posthuman rights since, in liberal societies, the law is meant to apply equally to all, no matter how rich or poor, powerful or powerless, educated or ignorant, enhanced or unenhanced.[4] Other thinkers who are sympathetic to transhumanist ideas, such as philosopher Russell Blackford, have also objected to the appeal to tradition, and what they see as alarmism, involved in Brave New World-type arguments.[100]

Dehumanization (Frankenstein argument)

Fichier:The Young Family.jpgAustralian artist Patricia Piccinini's concept of what human-animal hybrids might look like are provocative creatures which are part of a sculpture entitled "The Young Family," produced to address the reality of such possible parahumans in a compassionate way. Transhumanists would call for the recognition of self-aware parahumans as persons.Biopolitical activist Jeremy Rifkin and biologist Stuart Newman accept that biotechnology has the power to make profound changes in organismal identity. They argue against the genetic engineering of human beings, because they fear the blurring of the boundary between human and artifact.[86][101] Philosopher Keekok Lee sees such developments as part of an accelerating trend in modernization in which technology has been used to transform the "natural" into the "artifactual".[102] In the extreme, this could lead to the manufacturing and enslavement of "monsters" such as human clones, human-animal chimeras or bioroids, but even lesser dislocations of humans and non-humans from social and ecological systems are seen as problematic. The film Blade Runner (1982), the novels The Boys From Brazil (1978) and The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) depict elements of such scenarios, but Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein is most often alluded to by critics who suggest that biotechnologies could create objectified and socially-unmoored people and subhumans. Such critics propose that strict measures be implemented to prevent what they portray as dehumanizing possibilities from ever happening, usually in the form of an international ban on human genetic engineering.[103]

Writing in Reason magazine, Ronald Bailey has accused opponents of research involving the modification of animals as indulging in alarmism when they speculate about the creation of subhuman creatures with human-like intelligence and brains resembling those of Homo sapiens. Bailey insists that the aim of conducting research on animals is simply to produce human health care benefits.[104]

A different response comes from transhumanist personhood theorists who object to what they characterize as the anthropomorphobia fueling some criticisms of this research, which science writer Isaac Asimov termed the "Frankenstein complex". They argue that, provided they are self-aware, human clones, human-animal chimeras and uplifted animals would all be unique persons deserving of respect, dignity, rights and citizenship. They conclude that the coming ethical issue is not the creation of so-called monsters but what they characterize as the "yuck factor" and "human-racism" that would judge and treat these creations as monstrous.[21][52]

Specter of coercive eugenicism (Eugenics Wars argument)

Some critics of transhumanism allege an ableist bias in the use of such concepts as "limitations", "enhancement" and "improvement". Some even see the old eugenics, social Darwinist and master race ideologies and programs of the past as warnings of what the promotion of eugenic enhancement technologies might unintentionally encourage. Some fear future "eugenics wars" as the worst-case scenario: the return of coercive state-sponsored genetic discrimination and human rights violations such as compulsory sterilization of persons with genetic defects, the killing of the institutionalized and, specifically, segregation from, and genocide of, "races" perceived as inferior.[105] Health law professor George Annas and technology law professor Lori Andrews are prominent advocates of the position that the use of these technologies could lead to such human-posthuman caste warfare.[103][106]

For most of its history, eugenics has manifested itself as a movement to sterilize against their will the "genetically unfit" and encourage the selective breeding of the genetically fit. The major transhumanist organizations strongly condemn the coercion involved in such policies and reject the racist and classist assumptions on which they were based, along with the pseudoscientific notions that eugenic improvements could be accomplished in a practically meaningful time frame through selective human breeding. Most transhumanist thinkers instead advocate a "new eugenics", a form of egalitarian liberal eugenics.[107] In their 2000 book From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice, (non-transhumanist) bioethicists Allen Buchanan, Dan Brock, Norman Daniels and Daniel Wikler have argued that liberal societies have an obligation to encourage as wide an adoption of eugenic enhancement technologies as possible (so long as such policies do not infringe on individuals' reproductive rights or exert undue pressures on prospective parents to use these technologies) in order to maximize public health and minimize the inequalities that may result from both natural genetic endowments and unequal access to genetic enhancements.[108] Most transhumanists holding similar views nonetheless distance themselves from the term "eugenics" (preferring "germinal choice" or "reprogenetics")[96] to avoid having their position confused with the discredited theories and practices of early-20th-century eugenic movements.[109]

Existential risks (Terminator argument)

Struck by a passage from Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski's anarcho-primitivist manifesto (quoted in Ray Kurzweil's 1999 book, The Age of Spiritual Machines[10]), computer scientist Bill Joy became a notable critic of emerging technologies.[110] Joy's 2000 essay "Why the future doesn't need us" argues that human beings would likely guarantee their own extinction by developing the technologies favored by transhumanists. It invokes, for example, the "grey goo scenario" where out-of-control self-replicating nanorobots could consume entire ecosystems, resulting in global ecophagy.[111] Joy's warning was seized upon by appropriate technology organizations such as the ETC Group. Related notions were also voiced by self-described neo-luddite Kalle Lasn, a culture jammer who co-authored a 2001 spoof of Donna Haraway's 1985 Cyborg Manifesto as a critique of the techno-utopianism he interpreted it as promoting.[112] Lasn argues that high technology development should be completely relinquished since it inevitably serves corporate interests with devastating consequences on society and the environment.[113]

In his 2003 book Our Final Hour, British Astronomer Royal Martin Rees argues that advanced science and technology bring as much risk of disaster as opportunity for progress. However, Rees does not advocate a halt to scientific activity; he calls for tighter security and perhaps an end to traditional scientific openness.[114] Advocates of the precautionary principle, such as the Green movement, also favor slow, careful progress or a halt in potentially dangerous areas. Some precautionists believe that artificial intelligence and robotics present possibilities of alternative forms of cognition that may threaten human life.[115] The series' doomsday depiction of the emergence of an A.I. that becomes a superintelligence - Skynet, a malignant computer network which initiates a nuclear war in order to exterminate the human species, has been cited by some involved in this debate.[116]

Transhumanists do not necessarily rule out specific restrictions on emerging technologies so as to lessen the prospect of existential risk. Generally, however, they counter that proposals based on the precautionary principle are often unrealistic and sometimes even counter-productive, as opposed to the technogaian current of transhumanism which they claim is both realistic and productive. In his television series Connections, science historian James Burke dissects several views on technological change, including precautionism and the restriction of open inquiry. Burke questions the practicality of some of these views, but concludes that maintaining the status quo of inquiry and development poses hazards of its own, such as a disorienting rate of change and the depletion of our planet's resources. The common transhumanist position is a pragmatic one where society takes deliberate action to ensure the early arrival of the benefits of safe, clean, alternative technology rather than fostering what it considers to be anti-scientific views and technophobie .[117]

One transhumanist solution proposed by Nick Bostrom is differential technological development, in which attempts would be made to influence the sequence in which technologies developed. In this approach, planners would strive to retard the development of possibly harmful technologies and their applications, while accelerating the development of likely beneficial technologies, especially those that offer protection against the harmful effects of others.[41]

Aperçu du transhumanisme

Pic de la Mirandole appelait déjà l'homme à sculpter sa propre statue et même avant lui Plotin : « Si tu ne vois pas encore ta propre beauté, fais comme le sculpteur d’une statue qui doit devenir belle : il enlève ceci, il gratte cela… De la même manière, toi aussi, enlève tout ce qui est superflu, redresse ce qui est oblique » (Énnéades).

Le terme transhumanisme a, quant à lui, été introduit par Julian Huxley en 1957, bien que le concept qu'il désignait diffère sensiblement de celui auquel les transhumanistes font référence depuis les années 1980.

Le transhumanisme s'est vu donner sa définition moderne par le philosophe Max More : « Le transhumanisme est une classe de philosophies qui tentent de nous guider vers une condition post-humaine. Le transhumanisme partage de nombreux éléments avec l'humanisme, ce qui inclut du respect pour la raison et la science, un attachement au progrès, et une valorisation de l'existence humaine (ou transhumaine)… Le transhumanisme diffère de l'humanisme en reconnaissant et en anticipant les altérations radicales de la nature et les possibilités de nos vies qui résultent de diverses sciences et technologies […] » [1]

Dr. Anders Sandberg croit que « le transhumanisme est la philosophie qui dit que nous pouvons et devrions nous développer à des niveaux supérieurs à la fois physiquement, mentalement et socialement, en utilisant des méthodes rationnelles » tandis que Dr. Robin Hanson croit que « le transhumanisme est l'idée que les nouvelles technologies vont probablement tellement modifier le monde d'ici un siècle ou deux que nos descendants ne seront plus 'humains' sous de nombreux aspects ».

Pour résumer la FAQ Transhumaniste (2.1), un des documents transhumanistes les plus reconnus, le transhumanisme est défini comme suit:

- La promotion de l'amélioration de la condition humaine à travers des technologies d'amélioration de la vie, comme l'élimination du vieillissement et l'augmentation des capacités intellectuelles, physiques ou psychologiques.

- L'étude des bénéfices, dangers et de l'éthique de la mise en œuvre de ces technologies.

Le transhumanisme et la technologie

Les transhumanistes encouragent en général les technologies modernes, y compris certaines qui prêtent à controverse, comme le génie génétique appliqué aux humains, ainsi que des technologies futuristes telles que le téléchargement d'un esprit humain vers une simulation exécutée par un ordinateur.

Typiquement, les transhumanistes pensent que les avancées rapides des technologies conduiront dans un avenir proche à la création d'une intelligence artificielle dont les capacités dépasseront celles des humains, et que cela conduira inexorablement à un progrès radical dans des domaines comme la nanotechnologie et l'ingénierie à l'échelle sous-moléculaire.

Certains analystes observent que le rythme du développement technologique accuse une augmentation régulière, ce qui conduit de nombreux futuristes à spéculer que les cinquante prochaines années vont conduire à des avancées technologiques radicales. Par conséquent, ils pensent qu'un nouveau paradigme pour penser l'avenir de l'humanité a commencé à prendre forme. La condition humaine, disent-ils, n'est pas aussi constante qu'elle l'a semblé, et des innovations futures autoriseront les humains à transformer leurs caractéristiques physiques, émotionnelles et cognitives comme ils le désireront.

Le transhumanisme soutient que cela est bon, et que les humains peuvent et devraient devenir plus qu'humains.

« Le transhumanisme est plus qu'une simple croyance abstraite que nous sommes sur le point de transcender nos limitations biologiques au travers de la technologie. C'est aussi une tentative pour réévaluer la définition entière de l'être humain comme on la conçoit habituellement », dit le philosophe transhumaniste Nick Bostrom. « Et c'est un engagement à entreprendre une approche constructive et à long terme concernant notre nouvelle situation. »

Plus récemment, Jacques Attali, dans Une brève histoire de l'avenir, paru en 2006, voit dans le transhumain la porte de sortie de l'hyperempire, un monde chaotique qu'il décrit comme dominé par les mutations technologiques et débouchant sur un conflit généralisé vers 2050.

Les Lumières et les racines humanistes

Suivant l'influence politique, philosophique et morale des Lumières, le transhumanisme cherche à construire à partir de la base de connaissances globales, pour le bien de l'ensemble de l'humanité.

Dérivé en partie de la tradition philosophique de l'humanisme séculaire, le transhumanisme affirme que les humains ne devraient pas être vus comme le « centre » de l'univers moral, et qu'il n'y a pas de force surnaturelle qui guide l'humanité. Bien qu'étant un mouvement très diversifié, le transhumanisme tend vers l'usage d'arguments rationnels et d'observations empiriques de phénomènes naturels. De nombreuses manières, les transhumanistes prennent part dans une culture de science et de raison, et sont guidés par des principes de valorisation de la vie.

En particulier, le transhumanisme cherche à appliquer la raison, la science et la technologie dans le but de lutter contre la pauvreté, la maladie, le handicap, la malnutrition et les gouvernements dictatoriaux dans le monde. De nombreux transhumanistes vantent activement le potentiel qu'offrent les technologies futures et les systèmes sociaux innovants pour améliorer la qualité de la vie, tout en permettant à la réalité physique de la condition humaine de satisfaire les promesses d'égalité légale et politique en éliminant les barrières congénitales mentales et physiques.

Au-delà de l'humanisme

Le transhumanisme prétend qu'il existe un impératif éthique pour que les humains recherchent le progrès et l'amélioration. Si l'humanité entre dans une phase post-Darwinienne de l'existence, dans laquelle les humains contrôlent l'évolution, alors les mutations aléatoires seront remplacées par des changements guidés par la raison, la morale et l'éthique.

À cette fin, les transhumanistes s'engagent dans des approches interdisciplinaires pour comprendre et évaluer les possibilités afin de surmonter les limitations biologiques. Cela inclut l'usage de nombreux domaines et sous-domaines de la science, de la philosophie, de l'histoire naturelle et de la sociologie.

Manifestes transhumanistes

La première déclaration transhumaniste fut formulée par FM-2030 dans son Upwingers Manifesto en 1978, comme une vue optimiste de l'avenir et une référence à l'idée politique que ni la gauche ni la droite n'apporteraient les changements nécessaires à un avenir positif.

En 1990, un code plus formel et concret pour les transhumanistes libertariens prend la forme des Principes transhumanistes d'Extropie (Transhumanist Principles of Extropy), l'extropianisme étant une synthèse du transhumanisme et du néolibéralisme.

Et, finalement, en 1999, l'Association transhumaniste mondiale, dont les membres sont dans leur immense majorité des centristes convaincus des vertus de la démocratie libérale, rédige et adopte la Déclaration transhumaniste (Transhumanist Declaration):

- L’avenir de l’humanité va être radicalement transformé par la technologie. Nous envisageons la possibilité que l’être humain puisse subir des modifications, tel que son rajeunissement, l’accroissement de son intelligence par des moyens biologiques ou artificiels, la capacité de moduler son propre état psychologique, l’abolition de la souffrance et l’exploration de l’univers.

- On devrait mener des recherches méthodiques pour comprendre ces futurs changements ainsi que leurs conséquences à long terme.

- Les transhumanistes croient que, en étant généralement ouverts à l’égard des nouvelles technologies et en les adoptant, nous favoriserions leur utilisation à bon escient au lieu d’essayer de les interdire.

- Les transhumanistes prônent le droit moral, pour ceux qui le désirent, de se servir de la technologie pour accroître leurs capacités physiques, mentales ou reproductives et d’être davantage maîtres de leur propre vie. Nous souhaitons nous épanouir en transcendant nos limites biologiques actuelles.

- Pour planifier l’avenir, il est impératif de tenir compte de l’éventualité de ces progrès spectaculaires en matière de technologie. Il serait catastrophique que ces avantages potentiels ne se matérialisent pas à cause de la technophobie ou de prohibitions inutiles. Par ailleurs, il serait tout aussi tragique que la vie intelligente disparaisse à la suite d’une catastrophe ou d’une guerre faisant appel à des technologies de pointe.

- Nous devons créer des forums où les gens pourront débattre en toute rationalité de ce qui devrait être fait ainsi que d’un ordre social où l’on puisse mettre en œuvre des décisions responsables.

- Le transhumanisme englobe de nombreux principes de l’humanisme moderne et prône le bien-être de tout ce qui éprouve des sentiments qu’ils proviennent d’un cerveau humain, artificiel, post-humain ou animal. Le transhumanisme n’appuie aucun politicien, parti ou programme politique.

Alastair Reynolds aborde également le transhumanisme au travers de son cycle des Inhibiteurs, principalement par ses personnages Ultras et Conjoineurs.

Notes

- ↑ a , b , c , d , e , f et g Nick Bostrom, « A history of transhumanist thought », dans Journal of Evolution and Technology, vol. 14, no 1, avril 2005 [texte intégral (page consultée le 2006-02-21)]

- ↑ a et b Andy Miah, « Posthumanism: A Critical History », dans Gordijn, B. & Chadwick, R., Medical Enhancements & Posthumanity. New York: Routledge, 2007 [texte intégral (page consultée le 21 février 2006)]

- ↑ a , b et c Francis Fukuyama, « The world's most dangerous ideas: transhumanism », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2004 [texte intégral (page consultée le 2008-11-14)]

- ↑ a et b Ronald Bailey, « Transhumanism: the most dangerous idea? », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2004 [texte intégral (page consultée le 20 février 2006)]

- ↑ Pic de la Mirandole (1463-1494), Discours sur la dignité de l’homme, cité par Jean Carpentier, Histoire de l’Europe, Points Seuil, Paris, 1990, pp. 224-225.

- ↑ Nikolai Berdyaev, « The Religion of Resusciative Resurrection. "The Philosophy of the Common Task of N. F. Fedorov" », dans {{{périodique}}} [texte intégral (page consultée le 4 janvier 2008)]

- ↑ Julian Huxley, « Transhumanism », dans {{{périodique}}}, 1957 [texte intégral]

- ↑ Marvin Minsky, « Steps toward artificial intelligence », dans {{{périodique}}}, 1960 [texte intégral]

- ↑ a et b Hans Moravec, « When will computer hardware match the human brain? », dans Journal of Evolution and Technology, vol. 1, 1998 [texte intégral (page consultée le 23 juin 2006)]

- ↑ a et b Raymond Kurzweil, The Age of Spiritual Machines, Viking Adult, 1999 (ISBN 0-670-88217-8) (OCLC 224295064)

- ↑ "new concepts of the Human"

- ↑ FM-2030, Are You a Transhuman?: Monitoring and Stimulating Your Personal Rate of Growth in a Rapidly Changing World, Viking Adult, 1989 (ISBN 0-446-38806-8) (OCLC 18134470)

- ↑ Robert Ettinger, Man into Superman, Avon, 1974, HTML (ISBN 0-380-00047-4)

- ↑ FM-2030, UpWingers: A Futurist Manifesto, John Day Co., New York, 1973 (ISBN 0-381-98243-2; disponible en eBook: FW00007527) (OCLC 600299)

- ↑ EZTV Media

- ↑ Ed Regis, Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition: Science Slightly Over the Edge, Perseus Books, 1990

- ↑ Natasha Vita-More, « Tranhumanist arts statement », dans {{{périodique}}}, 1982; révisé en 2003 [texte intégral (page consultée le 16 février 2006)]

- ↑ Drexler 1986

- ↑ Max More, « Principles of extropy », dans {{{périodique}}}, 1990–2003 [texte intégral (page consultée le 16 février 2006)]

- ↑ Max More, « Transhumanism: a futurist philosophy », dans {{{périodique}}}, 1990 [texte intégral (page consultée le 14 novembre 2005)]

- ↑ a , b et c James Hughes, « Report on the 2005 interests and beliefs survey of the members of the World Transhumanist Association », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2005 [[pdf] texte intégral (page consultée le 26 février 2006)]

- ↑ World Transhumanist Association, The transhumanist declaration, 2002

- ↑ World Transhumanist Association, « The transhumanist FAQ », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2002–2005 [[pdf] texte intégral (page consultée le 27 août 2006)]

- ↑ Anders Sandberg, « Definitions of Transhumanism », dans {{{périodique}}} [texte intégral (page consultée le 5 mai 2006)]

- ↑ a , b , c , d , e , f et g James Hughes, Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future, Westview Press, 2004 (ISBN 0-8133-4198-1) (OCLC 56632213)

- ↑ a et b Alyssa Ford, « Humanity: The Remix », Mai-Juin 2005, Utne Magazine. Consulté le 3 mars 2007

- ↑ William Saletan, « Among the Transhumanists », 4 juin 2006, Slate.com. Consulté le 3 mars 2007

- ↑ Extropy Institute, « Next Steps », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2006 [texte intégral (page consultée le 5 mai 2006)]

- ↑ Russel Blackford, « WTA changes its image », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2008 [texte intégral (page consultée le 18 novembre 2008)]

- ↑ H+ Magazine

- ↑ « Can Futurism Escape the 1990s? », dans {{{périodique}}}, 2008 [texte intégral (page consultée le 18 novembre 2008)]

- ↑ Stephen G. Post et Christopher Hook, Encyclopedia of Bioethics, Macmillan, New York, 2004, 2517–2520 p. (ISBN 0028657748) (OCLC 52622160) [présentation en ligne], « Transhumanism and Posthumanism »

- ↑ Langdon Winner, « Are Humans Obsolete? », Automne 2002, The Hedgehog Review. Consulté le 10 décembre 2007

- ↑ Gerhard Banse et al. et Christopher Coenen, Assessing Societal Implications of Converging Technological Development, edition sigma, Berlin, 2007, 141–172 p. (ISBN 978-3-89404-941-6) (OCLC 198816396) [présentation en ligne], « Utopian Aspects of the Debate on Converging Technologies »

- ↑ Why I Want to be a Posthuman When I Grow Up. Consulté le 10 décembre 2007

- ↑ Neil Badmington, « Theorizing Posthumanism », Hiver 2003, Cultural Critique. Consulté le 10 décembre 2007

- ↑ a et b N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, University Of Chicago Press, 1999 (ISBN 0226321460) (OCLC 186409073)

- ↑ Patrick Inniss, « Transhumanism: The Next Step? ». Consulté le 10 décembre 2007

- ↑ Harold Bailie, Timothy Casey et Langdon Winner, The Future of Human Nature, M.I.T. Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 385–411 p. (ISBN 0-262-524287-7), « Resistance is Futile: The Posthuman Condition and Its Advocates »

- ↑ a , b et c (en) Kurzweil, Raymond, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, Viking Adult, 2005 (ISBN 0-670-03384-7) (OCLC 224517172)

- ↑ a et b Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ The Abolitionist Society, « Abolitionism ». Consulté le 3 janvier 2007

- ↑ a et b Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ a et b Immortality Institute

- ↑ a et b Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Mormon Transhumanist Association

- ↑ (en) Raël, Oui au clonage humain: La vie éternelle grâce à la science, Quebecor, 2002 (ISBN 1903571057) (OCLC 226022543)

- ↑ a et b Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Tipler, Frank J., The Physics of Immortality, Doubleday, 1994 (ISBN 0-19-282147-4) (OCLC 16830384)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ a et b Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Davis, Erik, TechGnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information, Three Rivers Press, 1999 (ISBN 0-609-80474-X) (OCLC 42925424)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ TransVision 2004: Faith, Transhumanism and Hope Symposium

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Kurzweil, Raymond, The 10% Solution for a Healthy Life, Three Rivers Press, 1993

- ↑ (en) Kurzweil, Raymond, Fantastic Voyage: Live Long Enough to Live Forever, Viking Adult, 2004 (ISBN 1-57954-954-3) (OCLC 56011093)

- ↑ (en) Naam, Ramez, More Than Human: Embracing the Promise of Biological Enhancement, Broadway Books, 2005 (ISBN 0-7679-1843-6) (OCLC 55878008)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Roco, Mihail C. and Bainbridge, William Sims, eds., Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance, Springer, 2004 (ISBN 1402012543) (OCLC 52058285)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Moreno, Jonathan D., Mind Wars: Brain Research and National Defense, Dana Press, 2006 (ISBN 1932594167)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) O’Bryan, C. Jill, Carnal Art:Orlan’s Refacing, University of Minnesota Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-8166-4322-9) (OCLC 56755659)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Garreau, Joel, Radical Evolution: The Promise and Peril of Enhancing Our Minds, Our Bodies -- and What It Means to Be Human, Broadway, 2006 (ISBN 0767915038) (OCLC 68624303)

- ↑ (en) Max Dublin, Futurehype: The Tyranny of Prophecy, Plume, 1992 (ISBN 0-452-26800-1) (OCLC 236056666)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ a , b et c (en) Stock, Gregory, Redesigning Humans: Choosing our Genes, Changing our Future, Mariner Books, 2002 (ISBN 0-618-34083-1) (OCLC 51756081)

- ↑ (en) Bob Seidensticker, Futurehype: The Myths of Technology Change, Berrett-Koehler, 2006 (ISBN 1576753700) (OCLC 184967241)

- ↑ (en) Broderick, Damien, The Spike, Tom Doherty Associates, 1997 (ISBN 0-312-87781-1) (OCLC 45093893)

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Rifkin, Jeremy, Algeny: A New Word--A New World, Viking Adult, 1983

- ↑ a et b Newman, Stuart A., « Averting the clone age: prospects and perils of human developmental manipulation », dans J. Contemp. Health Law & Policy, vol. 19, 2003, p. 431 [[pdf] texte intégral (page consultée le 2008-09-17)]

- ↑ Modèle:Cite paper

- ↑ (en) Cole-Turner, Ronald, The New Genesis: Theology and the Genetic Revolution, Westminster John Knox Press, 1993 (ISBN 0-664-25406-3) (OCLC 26402489)

- ↑ (en) Peters, Ted, Playing God?: Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom, Routledge, 1997 (ISBN 0-415-91522-8) (OCLC 35192269)